Die Lebensmittel-Inflation: Warum die Situation vielleicht schlimmer wahrgenommen wird als sie wirklich ist

Die Inflationsraten befinden sich in vielen Volkswirtschaften der Welt auf dem höchsten Stand seit Jahrzehnten. Die Auswirkungen der Pandemie, Lieferkettenprobleme und militärische Konflikte haben die Weltwirtschaft vor zahlreiche Herausforderungen gestellt und als Folge davon sind Preissteigerungen bei lebenswichtigen Gütern wie Kraftstoffe und Lebensmittel zu verzeichnen. Und dies ist bereits bei den Verbrauchern zu spüren, wodurch sich die Lektüre des aktuellen Dunnhumby-Verbraucherpuls-Berichtes sehr trübsinnig anlässt1.

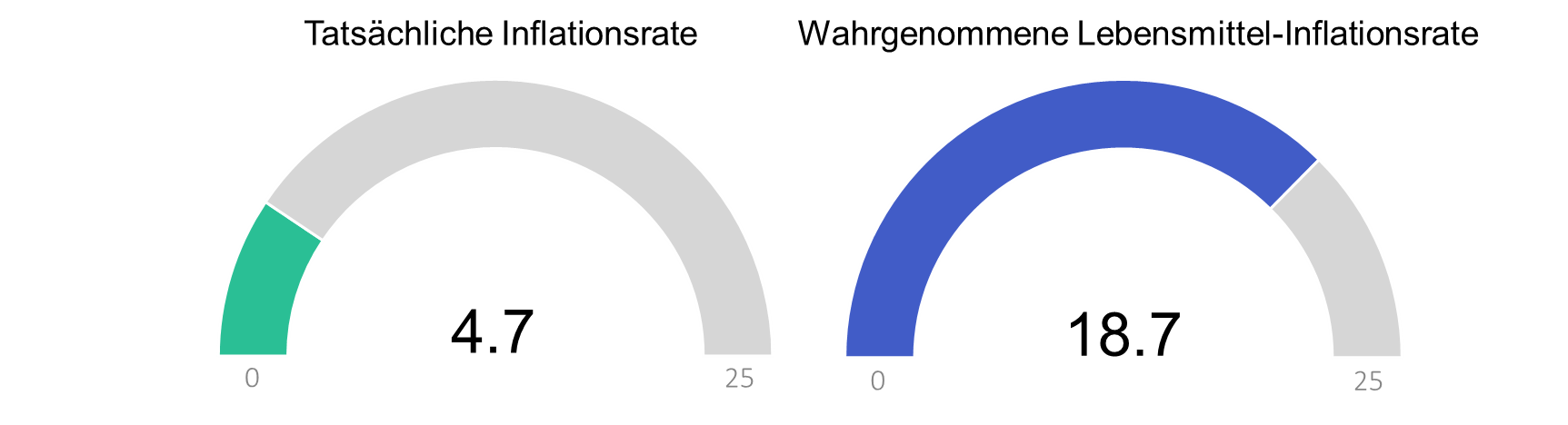

Wieviel davon ist jedoch auf die Wahrnehmung der Kunden zurückzuführen? Die nachfolgende Abbildung 1 stellt die weltweite Wahrnehmung der Lebensmittel-Inflation dar. Diese Wahrnehmung ist nahezu 4-mal so hoch wie der reale Wert der Lebensmittel-Inflation:

Abbildung 1: zeigt die tatsächliche globale Lebensmittel-Inflation auf der linken Seite und die wahrgenommene Lebensmittel-Inflation auf der rechten Seite. Die wahrgenommene Lebensmittel-Inflation fällt sehr viel höher aus als die tatsächliche. Die tatsächliche Lebensmittel-Inflation stammt von Tradingeconomics.com.

Es wird deutlich, dass die tatsächliche Lebensmittel-Inflation eine Sache ist, die wahrgenommene jedoch eine ganz andere. Dies legt nahe, dass Einzelhändler und Verbrauchsgüterhersteller die Lebensmittel-Inflation aus der Perspektive ihrer Kunden und nicht nur als Wirtschaftskennzahl betrachten müssen.

Dieser Beitrag beschäftigt sich mit den folgenden Fragen:

- Welche Märkte sind stärker besorgt?

- Wer ist stärker besorgt?

- Wann sind Kunden stärker besorgt?

- Was können Einzelhändler noch weiter tun?

Welche Märkte sind stärker besorgt?

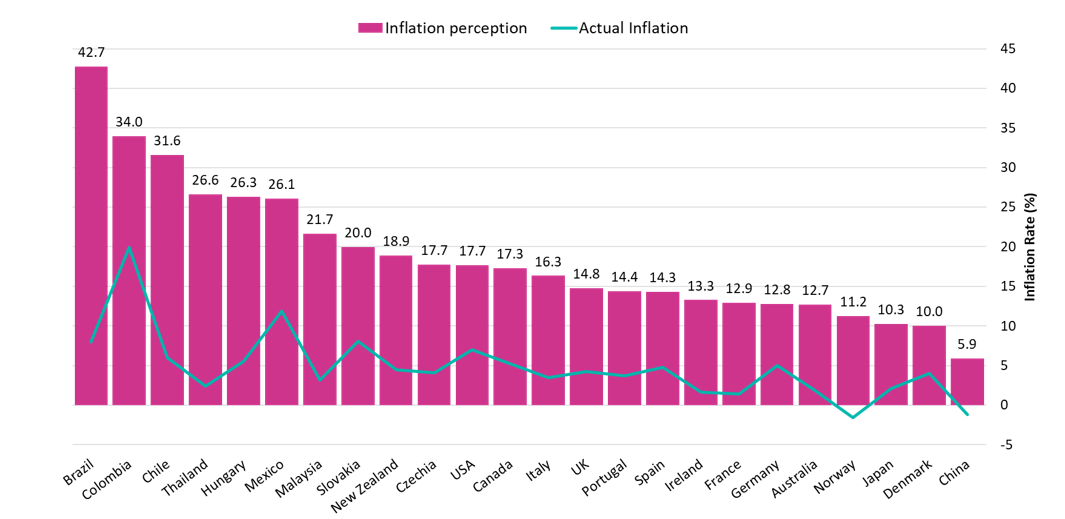

Die Inflation wird nicht auf der ganzen Welt gleich empfunden. Die nachfolgende Abbildung 2 stellt die wahrgenommene Lebensmittel-Inflation für die Dunnhumby-Hauptmärkte zusammen mit der realen Inflationsrate dar. Die wahrgenommene Lebensmittel-Inflation reichte von 42,7 % in Brasilien bis zu 5,9 % in China. Die Märkte, die im größeren Maße besorgt sind, umfassen allgemein gesehen Lateinamerika und Mitteleuropa.

Abbildung 2: veranschaulicht die wahrgenommene und tatsächliche Lebensmittel-Inflation für die DH-Hauptmärkte. Die Lebensmittel-Inflation wird nicht in allen Ländern gleich empfunden.

Selbst wenn man die reale Lebensmittel-Inflation von der wahrgenommenen abziehen würde, lägen die Überschätzungen durchschnittlich 14 Prozentpunkte höher (von 34,7 % für Brasilien bis zu 6 % für Dänemark). Das bedeutet, sogar wenn wir den Grad der realen Inflation berücksichtigen, ist die wahrgenommene Lebensmittel-Inflationsrate immer noch sehr hoch.

Wer ist stärker besorgt?

Der Verbraucherpuls-Bericht fand Hinweise darauf, dass Frauen etwas mehr als Männer über eine höhere wahrgenommene Inflationsrate besorgt sind (20 % der Frauen gegenüber 17 % der Männer). Außerdem gab es Anzeichen, dass die jüngere Bevölkerung die Lebensmittel-Inflation leicht höher einschätzt als ältere Leute (19 % bei 18-34-Jährigen und 16 % bei Menschen im Alter von 65 Jahren und darüber).

Dies passt zu einigen allgemeinen Inflationsdaten der Bank of Cleveland, USA, die herausgefunden hat, dass Frauen die allgemeine Preisinflation (Consumer Price Index, CPI) höher als Männer einschätzen2. Dies beruht nicht auf der Tatsache, dass Frauen tendenziell mehr Haushaltseinkäufe tätigen, da es auch einen deutlichen Unterschied zwischen alleinstehenden Frauen und alleinstehenden Männern gab. In der gleichen Studie wurde auch festgestellt, dass Geringverdiener, Alleinstehende, Nicht-Weiße und junge Menschen die allgemeine Inflation höher einschätzen.

Basierend auf Lebensmitteldaten aus den USA3, wurde zudem festgestellt, dass die Erwartungen von Verbrauchern an die allgemeine Inflation nicht auf den Anteil der Ausgaben, sondern vielmehr auf die Häufigkeit der Einkäufe zurückzuführen sind. Dies könnte eine wichtige zusätzliche Variable sein, um Kunden zu identifizieren, die möglicherweise mehr Unterstützung benötigen.

Wann sind Kunden stärker besorgt?

Kurzfristig gesehen und angesichts der aktuellen hohen Inflationsrate und dem Medieninteresse für die Inflation kann man erwarten, dass die Preise momentan in den Köpfen der Kunden sehr präsent sind. Wird es jedoch auf längere Sicht gesehen und wenn sich die Inflation stabilisiert hat, einen Zeitpunkt im Jahr geben, an dem die Inflation einen höheren Stellenwert einnimmt?

Es gibt eine interessante Tracker-Studie zur wahrgenommenen allgemeinen Inflation aus Dänemark4. In dieser Studie wurde festgestellt, dass die allgemeine Inflation in der Wahrnehmung im Juli am höchsten ist (und am geringsten im Februar, der Unterschied zwischen Februar und Juli liegt bei einem Prozentpunkt). In Dänemark liegt dies an den traditionelle Ausverkaufszeiten im Januar/Februar und den vermeintlich höheren Preisen in der langen Ferienzeit. Es könnte daran liegen, dass die Budgets der Kunden in den langen Sommerferien kleiner ausfallen als im übrigen Jahr.

Diese Daten sind wichtig, da die einzelnen Märkte mit ihnen jene Jahreszeiten ermitteln können, in denen die Kunden möglicherweise mehr Unterstützung benötigen, sobald die Inflation stabiler geworden ist.

Was können Einzelhändler noch weiter tun?

Letztlich, und vielleicht am wichtigsten, was können die Einzelhändler und Verbrauchsgüterhersteller noch im Hinblick auf die Inflation tun? Traditionell reagieren Unternehmen auf Inflation mit Preissteigerungen, Kosteneinsparungen (evtl. auch mit Qualitätseinsparungen) und verringerten Gewinnspannen5. Dunnhumby hat bereits einen umfangreichen Ratgeber zum Thema, wie man mit der Inflation umgeht, erstellt6, 7, 8. Wenn man jedoch das Ausmaß dieser Inflation betrachtet, sollte man vielleicht noch weitere Maßnahmen in Erwägung ziehen:

- 1. Kommunikation

Intensivere Kommunikation, welche auf die Problematik der Lebensmittel-Inflation eingeht. Erklären Sie, was zur Senkung von Preisen unternommen wird und wie die Kunden besser mit ansteigenden Preisen umgehen können. Viel wichtiger ist es jedoch, dass man darlegt, warum Preissteigerungen häufig außerhalb des Einflussbereiches eines Einzelhändlers liegen.9 Annahmen, die der Preisfairness zuwiderlaufen, sollten vermieden werden. In einer klassischen verhaltensökonomischen Studie wurde beispielsweise festgestellt, dass eine Preissteigerung für eine Schneeschaufel nach einem Schneesturm als unfair empfunden wird, auch wenn es aus wirtschaftlicher Sicht Sinn macht10.

- 2. Soziale Verantwortung von Unternehmen

Wie können Einzelhändler zeigen, dass sie sich um das Wohlbefinden ihrer Kunden kümmern? Eine weitere Empfehlung besteht darin, die soziale Verantwortung insbesondere für preisempfindliche Kunden zu erhöhen.9 Einzelhändler sollten zeigen, dass sie auf andere Weise zur Preisfairness beitragen, wenn die Preise ansteigen.

- 3. Coupons

Gemäß den Daten des weltweiten Verbraucherpuls-Berichtes greifen die Verbraucher auf der Suche nach Mehrwert mehrheitlich auf Coupons und Sonderangebote für Produkte, die regelmäßig eingekauft werden, zurück (47 %). Dabei ist zu beachten, dass es sich hierbei um Produkte handelt, die regelmäßig eingekauft werden. Somit sind Coupons für unrelevante Produkte nicht sehr hilfreich. Nutzen Sie die Möglichkeiten der Personalisierung– der Einsatz von Coupons hat eine lange Geschichte. In der großen Rezession stieg die Nutzung von Coupons insgesamt um 27 % an, die Verwendung von Internet-Coupons hingegen wuchs um 263 %.11 Dies könnte ein Indiz dafür sein, wie wichtig das Internet auch im Angesicht der Inflation werden könnte. Darüber hinaus ergab der Verbraucherpuls-Bericht, dass das zweithäufigste Verhalten bei der Suche nach Mehrwert „das Suchen im Internet nach den besten Angeboten“ (41 %) ist. Deshalb dürfte es unumgänglich sein, das Onlineangebot und die Apps für alle Bevölkerungsgruppen möglichst einfach zu gestalten.

- 4. Lebensmittelabfälle

Weltweit wird ein Drittel der für den menschlichen Konsum produzierten Lebensmittel weggeworfen12. Davon kommen 61 % der Lebensmittelabfälle aus Haushalten, 13 % aus dem Einzelhandel und die verbleibenden 26 % aus der Gastronomie13. Zwar stehen Lebensmittelabfälle im Zusammenhang mit Nachhaltigkeit (Energie und Wasser für Anbau und Transport von Lebensmitteln), sie können aber ebenso als ein Instrument zur Vermeidung einer Lebensmittel-Inflation dienen. Möglicherweise gibt es einige neue Möglichkeiten, Lebensmittelabfälle zu reduzieren. So könnte man beispielsweise eine dynamischere Preisgestaltung praktizieren, wenn Lebensmittel ihre beste Zeit hinter sich haben, wie z. B. in Form von Preisreduzierungen, um die Mengen von Lebensmittelabfällen in Geschäften zu verringern14. Man könnte die Kunden durch flexible Rezepte und Maßnahmen gegen Lebensmittelverschwendung dazu ermutigen, Gerichte mit Zutaten zuzubereiten, die sich gerade in ihrem Kühlschrank finden15. Jegliche Methoden, die helfen, Lebensmittelverschwendung zu vermeiden, werden nicht nur zur Nachhaltigkeit beitragen, sondern auch der Lebensmittel-Inflation entgegenwirken.

- 5. Treuepreise

Ein weiteres Konzept ist die „präzise Preisgestaltung“, bei der man den Preis neu kalkuliert, um die tatsächlichen Produktkosten für einen einzelnen Kunden widerzuspiegeln5. Wie die Autoren erläutern, „ist die präzise Preisgestaltung – die sehr zielgerichtet ist und es Managern ermöglicht, die Preise auf die tatsächlichen, aktuellen Kosten jedes Produktes und die tatsächliche, aktuelle Rentabilität jedes Kunden abzustimmen – für dieses instabile Umfeld maßgeschneidert“. Auch wenn dies für den Lebensmitteleinzelhandel, wo viele Preise knapp unter einem runden Euro, d. h. bei 0,99 Euro liegen, nicht perfekt geeignet ist, können vielleicht einzelne Elemente davon eingesetzt werden. Beispielsweise bieten einige Einzelhändler bereits unterschiedliche Preise für verschiedene Kunden basierend auf ihrer Treue an (z. B. niedrigere Preise für Tesco-Treuekartenbesitzer gegenüber Nicht-Treuekartenbesitzern). Besteht die Möglichkeit, weitere treueabhängige Segmentierungen vorzunehmen, z. B., indem Kunden mit einer stärkeren Händler- und Produkttreue bessere Angebote gemacht werden?

Zusammenfassung

In diesem Blog wird beleuchtet, welche Märkte, wer und wann ein Kunde am ehesten über eine Lebensmittel-Inflation besorgt sein könnte. Außerdem werden Methoden aufgezeigt, wie Einzelhändler und Verbrauchsgüterhersteller der gefühlten hohen Lebensmittel-Inflation entgegenwirken können. Vor allem wird verdeutlicht, inwiefern die wahrgenommene Lebensmittel-Inflation über die tatsächliche Lebensmittel-Inflation hinausgeht. Das bedeutet, dass die Lebensmittel-Inflation bis zu einem gewissen Grad im Auge des Betrachters liegen kann. Einzelhändler und Verbrauchsgüterhersteller müssen die Lebensmittel-Inflation aus der Sicht der Kunden betrachten, anstatt sich ausschließlich auf wirtschaftliche Daten zu verlassen.

References

1 Clements, D., Ciancio, D. & Brandt, D (März, 2022). Nine new insights on global shopping behaviours. https://www.dunnhumby.com/resources/blog/trends/en/nine-new-insights-on-global-shopping-behaviours

2 Bryan, M. & Venkatu, G. (2001). The curiously different inflation perspectives of men and women. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Commentary Series. Available at http://www.clev.frb.org/Research/ Com2001/1015.pdf

3 D’Acunto, F., Malmendier, U., Ospina, J. & Weber, M. (2021). Exposure to Grocery Prices and Inflation Expectations. Journal of Political Economy 129 (5)

4 Abildgren, K. & Kuchler, A. (2019). Revisiting the inflation perception conundrum, Danmarks Nationalbank Working Papers, No. 144, Danmarks Nationalbank, Copenhagen

5 Byrnes, J. & Wass, J. (Feb, 2022). Precision Pricing When Inflation Is Rising. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/02/precision-pricing-when-inflation-is-rising

6 Ciancio, D. and Llewellyn, C. (February, 2022). 20 actions that retailers should be taking during inflationary times. dunnhumby blog https://www.dunnhumby.com/resources/blog/all/en/20-actions-that-retailers-should-be-taking-during-inflationary-times/

7 Ciancio, D. (November 2021). The Best Customer First Strategies for Inflationary Times: Part One. dunnhumby blog https://www.dunnhumby.com/resources/blog/price-value/en/the-best-customer-first-strategies-for-inflationary-times/

8 Ciancio, D. and Llewellyn, C. (January, 2022). Customer First Business Practices for Inflationary Times: Part Two. dunnhumby blog https://www.dunnhumby.com/resources/blog/price-value/en/customer-first-business-practices-for-inflationary-times-part-two/

9 Lu, Z., Bolton, L., Ng, S., Chen, H. (2020) The Price of Power: How Firm’s Market Power Affects Perceived Fairness of Price Increases. Journal of Retailing. 96 (2):220–234.

10 Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.K. and Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a Constraint on Profit Seeking: Entitlements in the Market. The American Economic Review 76 (4): 728-741

11 Beatty, T.K.M. and Senauer, B. (2013). The New Normal? U.S. Food Expenditure Patterns and the Changing Structure of Food Retailing. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 95 (2): 318-324

12 Gustavsson, J., Cederberg, C. and Sonesson, U. (2011). Global food losses and food waste – Extent, causes and prevention. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

13 Forbes, H., Quested, T.. & O’Connor, C. (2021). Food Waste Index. United Nations Environment Programme https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021

14 Fan, T., Xu, C. and Tao, F. (2020). Dynamic pricing and replenishment policy for fresh produce. Computers & Industrial Engineering 139. 106127

15 Unilever (2021) https://www.unilever.com/news/news-search/2021/one-use-up-day-a-week-cuts-food-waste-by-third/

TOPICS

RELATED PRODUCTS

Amplify Customer understanding to create strategies that drive results

Customer First solutionsThe latest insights from our experts around the world

Retail Media: Aus der Sicht des Käufers

Wie Shopper Insights den Erfolg im Lebensmitteleinzelhandel vorantreiben